Versioning a Rails API

Written: Apr 5, 2017

It’s not old, it’s vintage.

This post was last updated some years ago and hasn’t been updated recently. Be aware that some of the content, tools, and techniques described may not be completely up-to-date.

by CommitStrip.com

API versioning is one of those topics that divides developers into two camps: those who just know that their way is the best way, and those that are confused by the first camp and would rather pass on the whole thing. Once we set aside the bikeshedding, there are sound, sane justifications for choosing one method over another, but in a lot of cases, discussions move from theoretical to hypothetical problems instead of worrying about making things that work.

The good news for Rails developers is that adding versions to an existing application doesn’t have to be painful. If you know what to do, you can implement it and maintain it with little effort.

In this article, we’ll look at what you get by versioning your API, why you need to think really hard before deciding not to, and how to update your application to make it work.

Hey, is this really necessary?

Short answer: probably.

Longer answer: The purpose of versioning is to offer guarantees about your interface even as development continues. By not building those guarantees into your application, you’re assuming personal responsibility for ensuring that client and server remain in lock step at all times. That’s a difficult promise to keep in any of the following scenarios:

- You plan to introduce breaking changes in the future.

- Any of your clients are installable software including desktop and mobile applications.

- Third-party developers will be using your interface - with or without your support.

Even in cases where the API is private and you control development and installation of both the clients and the server, versioning can mean being able to roll out changes gradually as they’re ready and without as much orchestration required during deployment.

So yes, unless you’re building a classic Rails monolith (client is JS sprinkles or deployed as an asset of the application) you probably do need to version your API. Just because it sucks, doesn’t mean you can skip it if your app really needs it.

Selecting an interface strategy

Once you’ve decided to version an API, you’re essentially providing paths to access different representations of the same resource in parallel. So a request for version 1 of a given object might produce a very different response than version 6, even though the underlying state is the same. When we speak about RESTful APIs, we need a way for clients to specify which version of an endpoint is being requested, so that limits us to a relatively small set of possible options.

- Hostname or subdomain: via multiple hostnames e.g.

v3.api.example.com - URL segment: a version slug in the resource identifier, e.g.

/v1/users/100 - HTTP header: a custom header or MIME type parameter, e.g.

Accept: application/vnd.example.com; version=1 - Query parameter: via a query parameter, e.g.

/users/100?v=1

Each of these methods has its advantages and disadvantages. Many consider using a request header, for example, as the most technically sound technique for a RESTful service since the URI for a given resource remains consistent regardless of the version. The most common method, though, and one that’s certainly easier to test is probably using a version slug in the URL. That’s the strategy we’ll be using for the examples below, but understand that in all cases, the implementation will be similar in most respects.

Implementing Multiple Versions

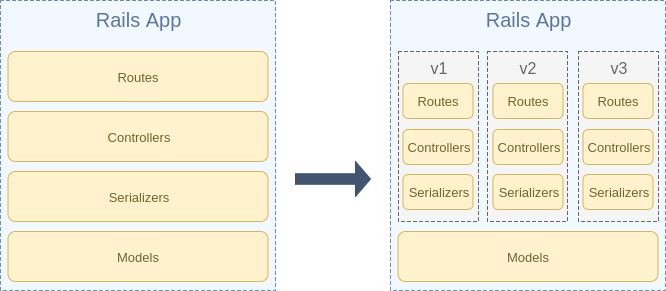

A versioned API application needs to be partitioned so that it can render different resource representations based on the requested version. That’s going to have an effect on any code involved in accepting HTTP requests and rendering responses, and in a prototypical Rails API application, that means the routes, controllers, and serializers as well as any tests that touch these. In contrast, models and other core application logic should specifically not be versioned in the same way. Any changes made to them over the lifetime of the application will generally need to be backward compatible. The diagram below gives a conceptual overview of how our example application will need to change.

Suppose we have a really simple blogging application as an example with two resources: posts and comments.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

# config/routes.rb

Rails.application.routes.draw do

resources :posts do

resources :comments

end

end

We can start on the path to versioning by updating the routes file to wrap the existing endpoints in a new namespace corresponding to version 1. The example below shows how to use a routing concern to cut down on duplication.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

# config/routes.rb

Rails.application.routes.draw do

concern :api_base do

resources :posts do

resources :comments

end

end

namespace :v1 do

concerns :api_base

end

end

Now we come to the job of refactoring the application so that it looks like the right-hand side of the diagram. We’ll need to move and update source files to reflect the namespacing we just defined in the routes file. The changes we need to make are repetitive and mechanical, so if it helps, it’s not a bad idea to begin by updating tests and letting them guide you through the remaining steps.

- Create

v1/subfolders underapp/controllers,app/serializers,test/controllers, andtest/serializers. - Move the source files to be versioned under the new subfolders using

mvorgit mv. - Namespace the affected classes. Ex:

PostsControllerbecomesV1::PostsController. - Optionally, you can also create namespaced parent classes. Ex:

class V1::BaseSerializer < ApplicationSerializer. - Namespace test definitions with the correct versioned class name. Ex:

describe PostsControllerbecomesdescribe V1::PostsController. - Update routing URL helper methods to the new versioned names. Ex:

post_urlbecomesv1_post_url. - Update resources interpreted as routes to use versioned URL helpers. Ex:

location: @postbecomeslocation: v1_post_url(@post).

It wasn’t pretty, but you should now have version 1 of your API up and running. Creating a new version 2 that exists independently will follow much the same process. First, you’ll define a new routing namespace similar to the one we created before.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

# config/routes.rb

Rails.application.routes.draw do

concern :api_base do

resources :posts do

resources :comments

end

end

namespace :v2 do

concerns :api_base

end

namespace :v1 do

concerns :api_base

end

end

And then you’ll need to prepare the new versions of the source files to

- Recursively copy all the

v1/source folders holding your controllers, serializers, and tests tov2/siblings. - Find and replace all instances of

v1|V1in the new source files withv2|V2.

This much copying and pasting of basically identical chunks of code should make you feel uneasy. As good codebase citizens, we’d prefer to share functionality some other way - through inheritance, mixins, composition, anything but this. But bear in mind that each of these versions needs to stand on its own without the risk of changes to one affecting another. That’s the reason for separating the endpoints and their tests through wholesale copying of code. And while I’m still looking at Rails engines and other alternative methods of implementing versioning, this is the least-worst of the options I’ve tried so far.